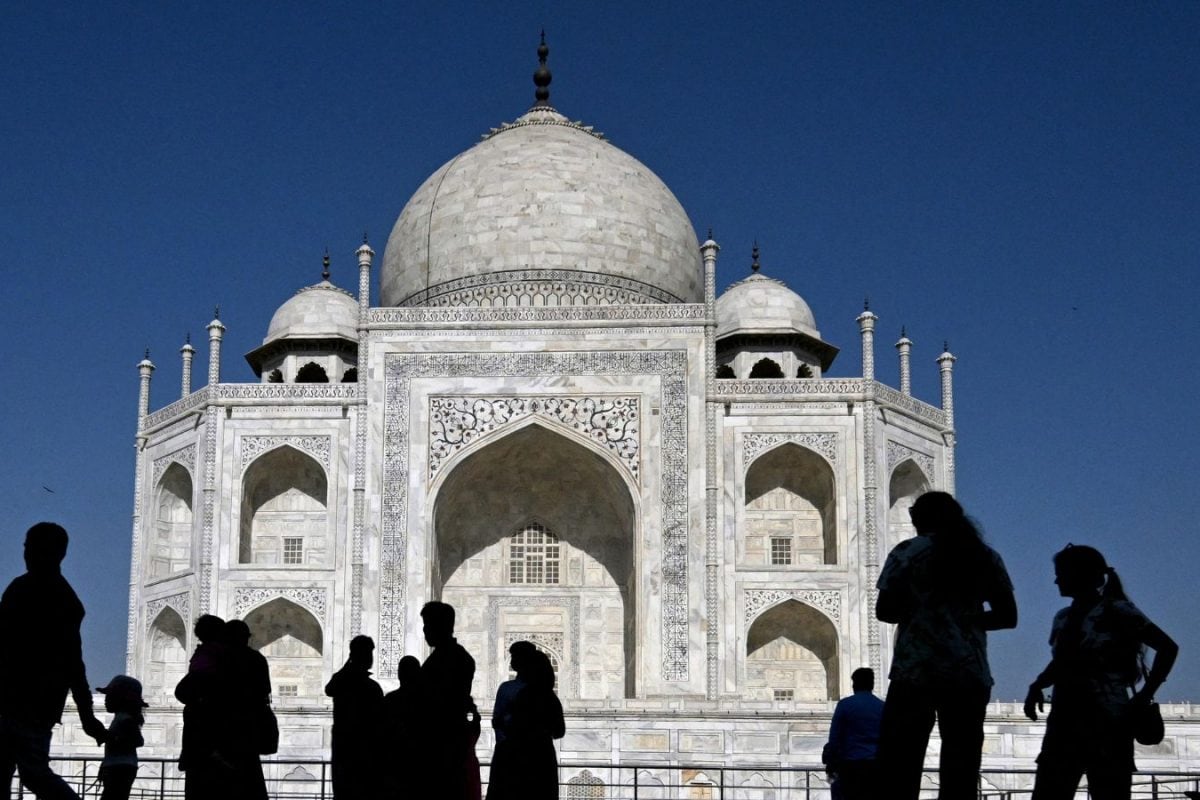

A recent analysis based on the World Resources Institute's (WRI) Aqueduct data indicates that the Taj Mahal is facing severe water scarcity, which is contributing to increased pollution and the depletion of groundwater levels, thereby damaging the iconic mausoleum. The analysis highlights that as many as 73% of all non-marine UNESCO World Heritage Sites, including several in India, are exposed to at least one severe water risk, such as water stress, drought, river or coastal flooding, with 21% of them facing dual problems of having too much water one year, and too little during another.

The Taj Mahal exemplifies how water stress is already taking a toll. Reduced groundwater levels around Agra, combined with increasing pollution in the Yamuna River, have accelerated degradation risks to the monument's white marble. Conservation experts point out that low groundwater not only affects structural integrity but also increases atmospheric pollutants that cling to the surface of the building, accelerating discoloration and corrosion. This underscores the urgent need for sustainable water management strategies to protect this cultural treasure.

The Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas monitors and evaluates hydrological risks. The global share of World Heritage Sites exposed to high-to-extremely high levels of water stress is projected to rise from 40% to 44% by 2050. The impacts will be far more severe in regions such as the Middle East and North Africa, parts of South Asia, and northern China, where existing water stress is exacerbated by extensive river regulation, damming, and upstream water withdrawals. In these regions, the combined pressures of infrastructure development and climate change pose a significant threat to both natural ecosystems and the cultural heritage they sustain.

India is the world's largest user of groundwater. Over the last 50 years, the number of borewells has grown from 1 million to 20 million. About 17% of groundwater blocks are overexploited, meaning the rate at which water is extracted exceeds the rate at which the aquifer can recharge, while 5% and 14% are at critical and semi-critical stages, respectively. Groundwater pollution and the effects of climate change, including erratic rainfall in the drier areas, put additional stress on groundwater resources, which serve about 85% of domestic water supply in rural areas, 45% in urban areas, and over 60% of irrigated agriculture.

The government of India regulates groundwater exploitation in water-stressed states through “notification” of highly overexploited blocks that restrict the development of new groundwater structures, except those for drinking water. However, only about 14% of the overexploited blocks in the country are currently notified. Integrated demand and supply-side solutions offer the best option for sustainable use. Weak regulatory action to limit demand for groundwater can hinder the success of programs in reversing groundwater depletion.

Water-related issues, including drought, scarcity, pollution, and flooding, have become a threat to many of the more than 1,200 UNESCO World Heritage Sites. In 2022, a massive flood closed down all of Yellowstone National Park and cost over $20 million in infrastructure repairs to reopen.